Back to Basics: A Tour of Yocto

Learn how BitBake and Poky work under the hood

Past blogs have mostly focused on creating recipes and trying to make a cool little project with a BeagleBone Black. Some tidbits and info have been sprinkled in on how BitBake and Poky work, but some information might still be a bit unclear regarding the Yocto Project and its tools it provides.

In this post, we’ll explore the history of Yocto, dive into what Poky is and how it works, and pull back the curtain on BitBake’s inner workings—from its layering and recipe syntax to its server, cooker, and task execution engine.

A Brief History of Yocto

Before Yocto, many embedded Linux developers were burdened with manually maintaining cross-compilation toolchains and build scripts, along with a vendor-provided kernel that they often had to cobble together and extend with custom device drivers. Those adventurous enough to fork the vendor’s kernel and create their own custom distribution found themselves doing double duty—integrating updates from the vendor into the kernel, while also handling any necessary userland tweaks. While toolchains existed, such as crosstool/crosstool-NG, BusyBox, and example efforts like uClinux, nothing was quite fully turnkey for building major distros for various hardware platforms.

In the early 2000s, as part of an effort to test the lightweight uClibc library for embedded systems, developers needed a way to build minimal Linux environments quickly and reproducibly. This need spurred the creation of an early build system that eventually evolved into Buildroot - one of the first open source tools specifically aimed at simplifying the development of custom embedded Linux distributions. Buildroot utilizes a kernel-style Makefile architecture that allowed existing devs who have already worked with the Linux kernel before to easily jump in and start making changes necessary for this to work with their own custom distro.

Around the same time, developers working on creating a replacement Linux distro for the SharpROM got word of this and used it to start the OpenZaurus Project. Many lessons were learned while working with the initial form of buildroot for the OpenZaurus project. The devs took note of these and decided to make a more generic build system that supported more variations of hardware. This new build system they created would eventually become known as OpenEmbedded - the build automation framework and cross-compile environment that is still used to this day by the Yocto Project.

OpenEmbedded

As described above, OpenEmbedded is a build automation framework and cross-compile environment for creating Linux-based distributions for almost any platform that supports Linux. However, it is best thought of as an entire ecosystem rather than just a framework. Its job is to build a repeatable, complete Linux distribution that can be run on both emulated devices and real hardware, depending on the target. It does this through a few key components and concepts.

BitBake

BitBake is probably the most important tool in the entire OpenEmbedded framework. It is a Python-based make-like build tool with a special focus on building packages and distributions for Linux. As such, it is better described as a generic task executor and operates using a task-oriented approach to building. Those familiar with Portage might see some similarities, as BitBake is heavily inspired by the Gentoo package system. BitBake’s core tasks include handling cross-compilation, managing inter-package dependencies, fetching upstream sources, and more - all while being architecture agnostic and self-contained. While BitBake may seem similar to make, it handles far more complex tasks like dependency management and cross-compilation.

Poky

Poky is the reference distribution for the Yocto Project. It’s essentially a working example that demonstrates best practices for building a complete Linux distribution. Poky combines a set of default layers (such as meta, meta-poky, and meta-yocto-bsp) along with BitBake recipes and configurations to provide a baseline system for real hardware platforms. You can think of this as the instructions for BitBake. It is showing you how to structure your layers and recipes, and give you a baseline to extend the system to create your own custom Linux distribution.

Recipes

Whereas make uses instruction sets called Makefiles, BitBake uses an analogous mechanism called recipes. Recipes, denoted by the .bb extension, provide the necessary metadata for BitBake to perform its task execution. A typical BitBake recipe consists of information about the package, version, dependencies, location of the source, compilation info, and where to install the package.

Configuration Files

Configuration files use the .conf extension and are used to define various configuration variables that handle the project’s overall build. Imagine you want to define where the location of your home directory should be on the system, or imagine you wish to define certain compiler tuning variables (e.g., soft float versus hard float on an armv7-a processor). Those overarching configurations are perfect for configuration files.

Classes

Classes, denoted with the .bbclass extension, allow us to share information that could be shared between metadata files. BitBake always includes the base.bbclass class automatically, and it provides initial definitions on how to fetch, unpack, configure, compile, install, and package tasks. You can inherit a class using the inherit directive and then extend or override its functionality. Classes are ideal when you want to encapsulate complex functionality and share it across BitBake recipes.

Includes

Classes aren’t the only way we can share metadata. Include files, denoted with the .inc extension, are another way to share common functionality. Whereas classes can be thought of as “blueprints” or modules in BitBake, encapsulating common functionality, include files can be thought of as a more straightforward mechanism of sharing common data. When you include or require an include, BitBake will literally perform a simple text replacement for you in that file. Includes are great when it comes to organizing your code and allowing you to keep a recipe clean without duplicating common configuration data.

Appends

Imagine you have a package that gets installed onto your system, and it is almost exactly what you want except for one small detail - say, where the package gets installed. This is where append files come into play. Denoted by the .bbappend extension, appends allow you to add to, or extend, an existing recipe without having to rewrite it entirely. For example, let’s say you wanted to change the OS name in /etc/os-release. You can simply create a .bbappend and tweak the relevant variable instead of duplicating the entire recipe.

Layers

Between recipes, configuration files, classes, includes, and append files, we have quite a selection of tools at our disposal for BitBake to execute on. The only thing left is to organize all these files. This is where layers come into play. A layer allows you to isolate all of these customizations from others, granting the developer modularity and flexibility over how to organize the metadata. You can, for example, separate Board Support Package (BSP)-specific customizations from GUI-specific ones, or create dependency chains and hierarchies where recipes from one layer take precedence over those in another.

Now that we have the basic concepts down, we can begin to look at writing example recipes for Yocto. As always, refer to the Yocto Project documentation for a deeper understanding of general syntax if you are ever confused at the below examples. I will attempt to explain along the way, but the Yocto Project does a great job at detailing every command and keyword that is available to use.

Understanding BitBake Recipes

At its core, BitBake is similar in spirit to classic build systems like make, but it is designed for cross-compiling and handling complex dependency trees. Recipes in BitBake are files that describe:

- What to build (metadata such as

SUMMARY,LICENSE, etc.) - Where to fetch the source code (

SRC_URI) - How to build it (tasks like

do_compile,do_install, etc.)

Each recipe is a series of Python statements, shell snippets, and variable definitions that together instruct BitBake on how to transform source code into a final package or image.

A Simple BitBake Recipe Example

Let’s start with a minimal example of a BitBake recipe for a simple “Hello World” application:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

# hello-world.bb

# Summarize what the recipe is

SUMMARY = "A simple Hello World application"

# List the license it adheres to

LICENSE = "MIT"

# Point BitBake to where it can find the file

SRC_URI = "file://hello.c"

# The default tasks include do_fetch, do_unpack, do_patch, do_configure, do_compile, do_install, etc.

# For simple recipes, you can override the compile and install tasks.

# Implement a simple compile task

do_compile() {

${CC} ${CFLAGS} ${WORKDIR}/hello.c -o hello

}

# Implement a simple install task to install this to /usr/bin

do_install() {

install -d ${D}${bindir}

install -m 0755 hello ${D}${bindir}

}

In this example, the recipe defines:

- Metadata:

SUMMARYandLICENSEprovide high-level information. - Source Retrieval:

SRC_URItells BitBake where to get the source. - Tasks:

do_compileanddo_installspecify how to build and install.

Recipe Building Tasks

When BitBake processes a recipe for a standard compiled application, it executes a series of tasks in a well‐defined order. These tasks handle fetching, unpacking, patching, configuring, compiling, installing, and packaging the software. The following table shows the typical flow for building a standard recipe:

| Task | Description |

|---|---|

| do_fetch | Retrieves the source code from the location specified by SRC_URI. |

| do_unpack | Unpacks the downloaded source archive into the working directory. |

| do_patch | Locates and applies any patch files defined in the recipe. |

| do_configure | Configures the source (e.g., runs ./configure) and sets up the build environment. |

| do_compile | Compiles the source code into binaries. |

| do_install | Installs the compiled binaries and related files into a temporary staging area (${D}). |

| do_package | Analyzes the staged files and splits them into packages based on metadata and file classification. |

| do_package_write_type | Writes package metadata specific to the package type (e.g., Debian, RPM, or IPK). |

| do_package_write | Finalizes the packaging process and creates the final package files. |

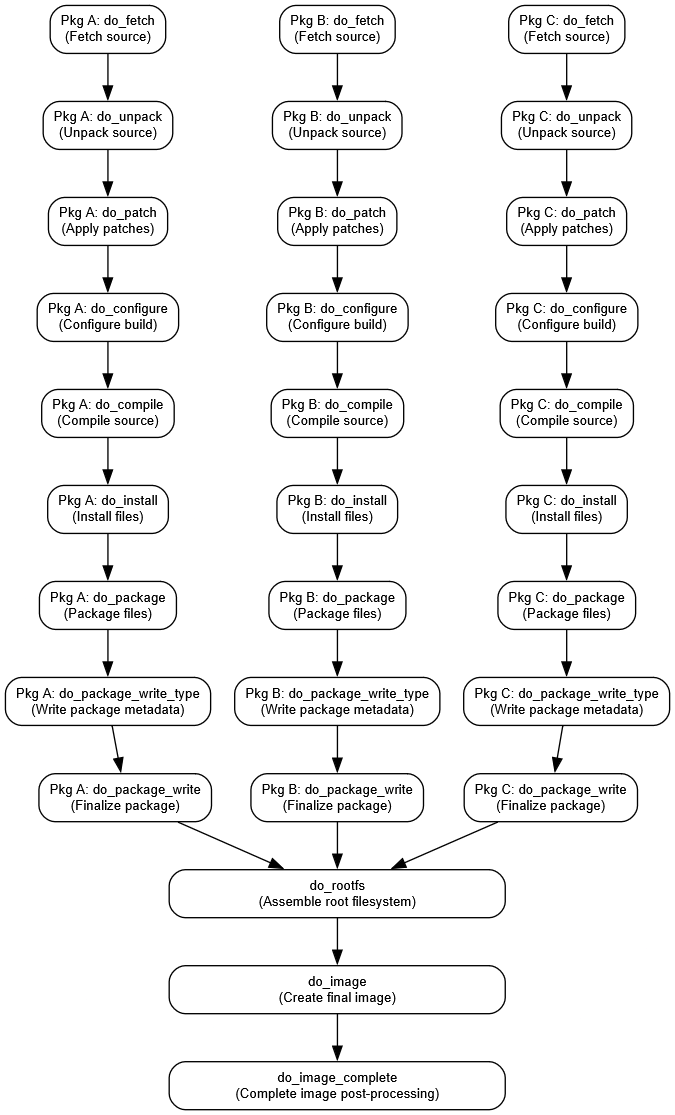

BitBake’s scheduler resolves task dependencies and executes these tasks in order, parallelizing where possible to optimize build times.

Image-Related Tasks

After individual recipes have been built and packaged, the build system assembles them into a complete Linux image. This process involves creating a root filesystem and then generating a final bootable image. It generally looks like this:

| Task | Description |

|---|---|

| do_rootfs | Assembles all the individual packages into a complete rootfs, setting up the file/directory structure. |

| do_image | Starts the image generation process, performing pre-processing on the rootfs to prepare for final packaging. |

| do_image_complete | Completes the image gen process by performing post-processing steps and finalizing the bootable image. |

These tasks integrate the outputs of the recipe builds into a consistent and bootable system image ready for deployment.

Note: The tasks shown above are usually executed by BitBake automatically. However, there are many other tasks you can call manually, as well as tasks for specialized components such as kernel development. You can find a list of them here.

Task Execution Flow

We can better visualize the overall task execution flow with an image. The following image showcases three packages that have no inter-depenencies on one another, so BitBake is free to execute these however it sees fit so long as the general execution flow remains the same.

A Real World BitBake Recipe Example

With a better understanding of how this all fits together, let’s take a look at a real world example of how OpenEmbedded devs wrote a recipe for gzip. The following was taken from the master branch of the meta repo. This particular example was split into two parts:

- gzip.inc: Contains common meta data and functions that apply to all versions.

- gzip_1.13.bb: Contains all version-specific parts of the recipe.

I will add line comments to help better explain what is going on:

gzip.inc

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

# High-level summary of the package

SUMMARY = "Standard GNU compressor"

# Brief description of what the package is

DESCRIPTION = "GNU Gzip is a popular data compression program originally written by Jean-loup Gailly for the GNU \

project. Mark Adler wrote the decompression part"

# URL for the program

HOMEPAGE = "http://www.gnu.org/software/gzip/"

# Categorizes the package within a section to make it easier for menu listings

SECTION = "console/utils"

# Inherit capabilities from autotools and texinfo

inherit autotools texinfo

# Disable assembly optimizations during the build

export DEFS = "NO_ASM"

# Configure various extra make options

EXTRA_OEMAKE:class-target = "GREP=${base_bindir}/grep"

EXTRA_OEMAKE:append:class-nativesdk = " GREP=grep"

EXTRA_OECONF:append:libc-musl = " gl_cv_func_fflush_stdin=yes "

# Append these additional steps to the do_install task:

do_install:append () {

if [ "${base_bindir}" != "${bindir}" ]; then

# Rename and move files into /bin (FHS), which is typical place for gzip

install -d ${D}${base_bindir}

mv ${D}${bindir}/gunzip ${D}${base_bindir}/gunzip

mv ${D}${bindir}/gzip ${D}${base_bindir}/gzip

mv ${D}${bindir}/zcat ${D}${base_bindir}/zcat

mv ${D}${bindir}/uncompress ${D}${base_bindir}/uncompress

fi

}

# Inherit the update-alternatives class to manage symlinks

inherit update-alternatives

# Setup alternatives for the gzip commands

ALTERNATIVE_PRIORITY = "100"

ALTERNATIVE:${PN} = "gunzip gzip zcat"

ALTERNATIVE_LINK_NAME[gunzip] = "${base_bindir}/gunzip"

ALTERNATIVE_LINK_NAME[gzip] = "${base_bindir}/gzip"

ALTERNATIVE_LINK_NAME[zcat] = "${base_bindir}/zcat"

# Export the shell to use for configuration tasks

export CONFIG_SHELL = "/bin/sh"

gzip_1.13.bb

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

# Include the common settings from gzip.inc

require gzip.inc

# Update the license info for version 1.13

# change to GPL-3.0-or-later in 2007/07. Previous GPL-2.0-or-later version is

# 1.3.12

LICENSE = "GPL-3.0-or-later"

# Define the source URI

SRC_URI = "${GNU_MIRROR}/gzip/${BP}.tar.gz \

file://run-ptest \

"

# Append a patch to fix an issue with paths

SRC_URI:append:class-target = " file://wrong-path-fix.patch"

# Checksum for the license above

LIC_FILES_CHKSUM = "file://COPYING;md5=1ebbd3e34237af26da5dc08a4e440464 \

file://gzip.h;beginline=8;endline=20;md5=6e47caaa630e0c8bf9f1bc8d94a8ed0e"

# provide additional package info for native builds

PROVIDES:append:class-native = " gzip-replacement-native"

# Declare runtime deps for the package tests

RDEPENDS:${PN}-ptest += "make perl grep diffutils"

# Extend the recipe to also build native and SDK variants

BBCLASSEXTEND = "native nativesdk"

# Inherit the ptest class to enable runtime testing

inherit ptest

# Define a custom ptest install task:

do_install_ptest() {

mkdir -p ${D}${PTEST_PATH}/src/build-aux

cp ${S}/build-aux/test-driver ${D}${PTEST_PATH}/src/build-aux/

mkdir -p ${D}${PTEST_PATH}/src/tests

cp -r ${S}/tests/* ${D}${PTEST_PATH}/src/tests

sed -e 's/^abs_srcdir = ..*/abs_srcdir = \.\./' \

-e 's/^top_srcdir = ..*/top_srcdir = \.\./' \

-e 's/^GREP = ..*/GREP = grep/' \

-e 's/^AWK = ..*/AWK = awk/' \

-e 's/^srcdir = ..*/srcdir = \./' \

-e 's/^Makefile: ..*/Makefile: /' \

-e 's,--sysroot=${STAGING_DIR_TARGET},,g' \

-e 's|${DEBUG_PREFIX_MAP}||g' \

-e 's:${HOSTTOOLS_DIR}/::g' \

-e 's:${BASE_WORKDIR}/${MULTIMACH_TARGET_SYS}::g' \

${B}/tests/Makefile > ${D}${PTEST_PATH}/src/tests/Makefile

}

# Provide the checksum for the gzip source tarball

SRC_URI[sha256sum] = "20fc818aeebae87cdbf209d35141ad9d3cf312b35a5e6be61bfcfbf9eddd212a"

The recipe is straightforward, yet slightly complex given some of the workarounds they had to deal with in order to get it to work in an embedded platform. It’s a great example of separating common, portable logic from version-specific logic. It showcases how to apply a patch, how to extend a typical do_install task, and even implements its own do_install_ptest task to handle a Makefile workaround to get tests working correctly.

OpenEmbedded repos contain a plethora of well-constructed recipes that you can use as a reference for building your own. I highly recommend reading some of the official source code as you continue your journey writing recipes for Yocto-based projects.

BitBake Layers: Default and Additional Layers

One of Yocto’s greatest strengths is its modular, layered architecture. Layers allow you to separate concerns and organize your build metadata. There are two broad categories of layers:

- Default Layers: These come with Poky and provide the core functionality needed for most builds. Examples include:

- meta: The base metadata.

- meta-poky: Additional configuration and recipes specific to the reference distribution.

- meta-yocto-bsp: Board Support Packages (BSP) for various hardware.

- Additional Layers: These are community-contributed or vendor-specific layers that add extra functionality, recipes, or BSPs. Some popular examples:

- meta-openembedded: A collection of recipes and classes that extend the core functionality.

- meta-freescale, meta-intel, etc.: Layers targeted at specific hardware.

Configuring Layers with bblayers.conf

The build system uses the conf/bblayers.conf file to know which layers to include in the build. A typical configuration might look like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

# conf/bblayers.conf

BBLAYERS ?= " \

/home/user/yocto/poky/meta \

/home/user/yocto/poky/meta-poky \

/home/user/yocto/poky/meta-yocto-bsp \

/home/user/yocto/meta-openembedded/meta-oe \

/home/user/yocto/meta-openembedded/meta-python \

"

Each path points to a directory containing BitBake metadata. By adding or removing layers from this file, you can easily tailor your build environment.

Let’s say you created your own custom layer called meta-foo, and inside meta-foo, you have the Hello World application written above. Your custom layer might look something like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

meta-foo/

├── conf

│ └── layer.conf

├── recipes-core

│ └── hello-world

│ └── hello-world.bb

└── README

We added a conf/layer.conf file so we could set priority in case we want to override popular utilities like installing your own custom version of gzip. It would look something like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

# We have a conf directory, so we add it to BBPATH

BBPATH .= ":${LAYERDIR}"

# We have recipes-* directories, so we add it to BBFILES

BBFILES += "${LAYERDIR}/recipes-*/*/*.bb"

# The name of our layer that we add to BBFILE_COLLECTIONS

BBFILE_COLLECTIONS += "meta-foo"

# Match all files whose paths begin with the layer directory for meta-foo

BBFILE_PATTERN_meta-foo = "^${LAYERDIR}/"

# Our priority level. Higher number = higher priority

BBFILE_PRIORITY_meta-foo = "10"

# States what layer(s) we depend on

LAYERDEPENDS_meta-foo = "core"

# States what version(s) we are compatible with

LAYERSERIES_COMPAT_meta-foo = "kirkstone"

Next, simply add it to the conf/bblayers.conf above as such:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

BBLAYERS ?= " \

/home/user/yocto/poky/meta \

/home/user/yocto/poky/meta-poky \

/home/user/yocto/poky/meta-yocto-bsp \

/home/user/yocto/meta-openembedded/meta-oe \

/home/user/yocto/meta-openembedded/meta-python \

/home/user/yocto/meta-foo \

"

And that’s it! You now have your own custom meta layer that you can work in and begin customizing your own embedded Linux OS using Yocto.

Note: If you haven’t already, please see my previous blog post on how to construct your own custom layer as it will outline the process in much greater detail.

Under the Hood of BitBake

While BitBake recipes and layers are visible to the user, there is a sophisticated engine under the hood that makes it all work. We’ll take a high level look at roughly what is going on behind the scenes:

The BitBake User Interface

The BitBake UI is the command-line interface that developers interact with. Assume you execute something like this on the command-line:

1

bitbake core-image-minimal

The UI does the following:

- Parses Command-Line Arguments: Determines which recipes or targets to build.

- Loads Configuration Files: Reads global configuration (e.g.,

conf/bitbake.conf) and machine-specific settings. - Initializes Logging and Debugging: Sets up the logging infrastructure for the build.

The BitBake Server and Cooker

Once the UI has handed off control, the BitBake server (often referred to as the Cooker) takes over. The Cooker is responsible for:

- Parsing Recipes: Loading the metadata from various layers and recipes.

- Constructing the Dependency Graph: Determining the order in which tasks must be executed.

- Managing Task Execution: Coordinating the execution of tasks (and their dependencies) in a controlled manner.

Task Execution and Build Control

Each BitBake recipe defines multiple tasks as described above in our task breakdown section. The BitBake build control system ensures that:

- Dependencies Are Respected: For example,

do_compilewon’t run untildo_configureis complete. - Parallel Execution Is Managed: Independent tasks from different recipes can be executed concurrently to speed up the build.

- Environment Variables and Metadata: Passed along and expanded during task execution.

Elizabeth Flanagan actually has an amazing write up on how a lot of this works, and I highly suggest reading it to gain some more insight on the inner workings of what is going on with the BitBake IPC. Instead of simply rewording her work, I encourage everyone to read her write up here. While it is slightly outdated, the core concepts still apply to this day - which is a testament to how much foresight the original devs had!

Wrapping Up

Thus concludes the high level overview of the history of the Yocto Project! Most likely you are overwhelmed and things still aren’t clear. Don’t worry! It is not easy jumping into such a complex build system, so you shouldn’t be expecting to understand everything right away.

The trick is to continue to read recipes and start customizing a standard build that the Yocto Project has provided to us. As you begin to customize your own embedded Linux OS, you’ll start to better understand how everything fits together. As you run into issues, refer to the recipes provided by the OpenEmbedded team as they will be some of the highest quaility examples available.

Further Reading

Some useful links that helped me when I first started out:

- Architecture of Open Source: Yocto

- Yocto Mega Manual

- Yocto Project Quick Build

- Yocto Reference Manual

- Variable names and their paths

Happy building!