Beginner's Journey into Device Trees

History and high level overview of device trees

ARM has become more popular than it ever has before, a lot in part thanks to mobile devices and their powerful chips running our day-to-day lives. It has been a powerhouse in the embedded world for many years, and there are now more ARM-based dev boards than before to help kickstart people’s adventures into a different architecture besides the trusty x86 behemoth that most use for their desktop computing environments…but even that is changing thanks to Apple spearheading ARM for the desktop user.

There are many ways where ARM and x86 are different, and many people like to point to the instruction set differences. However, one thing that commonly trips up many embedded developers first jumping into the embedded ARM world when attempting their BSP porting journey is the concept of device trees. For a modern developer working mostly in the x86 world, the concept probably feels a bit strange. “What do they do? Why do they exist? Why can’t ARM just do what x86 does?” A lot of the answers to these actually stems back to the history of computing, so I figured I’d take us on a trip back in time to see if it’s possible to better explain how we even got here in the first place.

Figure 1: Device Driver Development with Raspberry Pi - Device Tree

The most important thing to realize about this article is that I am merely giving a general overview and won’t be diving into the specifics. We’ll first go through the history of enumerating hardware peripherals, look at a basic example of a device tree, explain some of the building blocks, how the kernel uses it, and also talk about how a general dev might work with device trees. I won’t go deep into firmware hacking or a lot of the DT intrinsics. However, I’ll try to link helpful articles on these topics for anyone who wants to dive deeper at the end, like always.

Travel Back in Time

If you have only ever worked with modern x86, you might be under the impression that hardware shows up, the OS discovers it, drivers auto load, and life goes on. However, you are actually working in a world of ACPI tables, PCI enumeration, UEFI firmware, and decades of backwards compatibility abstracting the pain we all went through during the early years. If all you know is modern day x86, then from that perspective, device trees probably feel like a problem that has already been solved.

However, if we rewind far enough, we find that x86 was not always this way, and early computing environments actually looked much closer to today’s embedded ARM world.

Figure 2: A Brief History of CPUs: 31 Awesome Years of x86

Before the rise of the IBM PC and its clones, computers were largely bespoke systems. Manufacturers controlled the entire machine: the CPU, memory layout, peripherals, and the operating system itself. There was no expectation that an OS would boot on multiple hardware variants. If you bought a machine from a vendor, you ran their OS, built for that exact hardware.

When peripherals began to appear, they were not discoverable in any meaningful sense. As an end user, addresses, interrupts, and access mechanisms were fixed, or at least assumed to be fixed. The operating system “knew” where devices lived because that knowledge was hard-coded or documented as part of the platform itself, all defined by the manufacturer. Changing core components of the hardware often meant changing the entire OS with it.

In other words, hardware description was hard-coded inside the OS.

The early PC era did not immediately change this, either. It merely standardized it by convention. Early IBM PCs and compatibles relied on assumed layouts:

As mentioned before, the OS didn’t actually “discover” this hardware; it assumed it or left it up to the end-user to configure. Users manually ensured that devices didn’t conflict, effectively acting as the “hardware description layer” themselves. Configuration files, setup utilities, and printed IRQ tables were all part of making the system usable.

As the i386 era arrived and PCs exploded in popularity, this model began to strain. Clone manufacturers, add-in cards, and competing peripherals created increasing complexity. IRQ conflicts, DMA collisions, and overlapping address ranges were common. General-purpose operating systems like DOS, Unix and Linux now had to support an expanding and chaotic ecosystem.

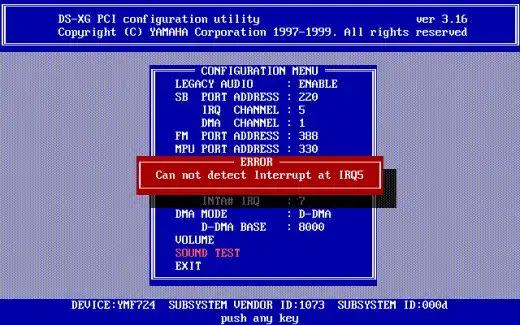

On early x86 PCs, hardware resources like IRQs and I/O port ranges were extremely limited and largely fixed by convention. For example, IRQ 4 was typically used by COM1, IRQ 7 was commonly used by LPT1, and Sound cards often defaulted to IRQ 5.

These assignments were not enforced by the system. Instead, they were configured manually using jumpers, DIP switches, and eventually via an interactive menu within the OS.

A very real and common failure mode looked like this:

A user installs a sound card configured for IRQ 7, but their main parallel port is also using IRQ 7. The system boots, but printing fails intermittently, audio stutters, or one of the devices silently stops working. Another would be when a user went to install a network card, but they also happened to have a sound card on the same IRQ.

Figure 3: How to Build an Awesome 386 Computer

From the operating system’s point of view, both devices appeared to be asserting the same interrupt line with no reliable way to determine which one actually generated the interrupt. The kernel had no authoritative hardware description, either. It simply trusted that the user had configured things correctly.

I/O port collisions were just as common. Two devices accidentally configured to use overlapping I/O ranges could corrupt each other’s registers, leading to behavior that was difficult to diagnose and nearly impossible to debug without deep hardware knowledge.

This pressure led to pushing the hardware industry to create a standardized hardware discovery mechanisms that were automatic and no longer relied on in-depth knowledge from the end user that many new users simply did not have.

PCI was the first major step: devices could enumerate themselves, expose vendor and device IDs, and be assigned resources dynamically. Eventually, ACPI formalized the contract between firmware and the operating system, providing structured tables that describe CPUs, memory, buses, power management, and platform devices.

From this point forward, x86 hardware description moved out of the OS and into firmware, where it became standardized and (mostly) consistent across vendors.

Embedded ARM platforms, a much newer platform compared to x86, simply never went through this consolidation phase.

Instead of one dominant platform with strong compatibility pressure, the ARM ecosystem grew around thousands of SoCs and board designs, each wired differently, often with minimal firmware and no universal discovery mechanism. In that environment, Linux still needed a way to be generic, so the hardware description moved out of the kernel again, this time into a structured data format: the device tree.

Looking at it through this lens, device trees are not a strange ARM-specific invention. They are a clean, explicit solution to a problem x86 once had, and later solved through decades of firmware and hardware standardization.

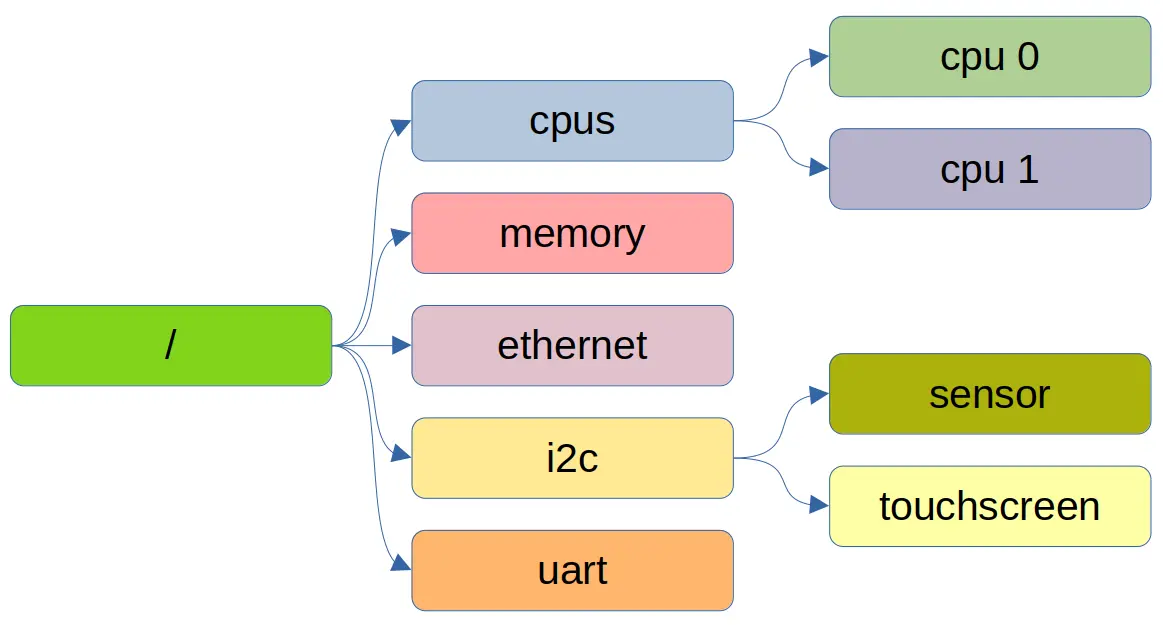

What is a Device Tree?

So now that we know a bit of the history of hardware discovery, what is a device tree, exactly? At a high level, a device tree is simply a structured data blob that describes the hardware layout of a system and is provided to the kernel at boot time. Its main job is to answer questions like:

What CPU(s) exist?

How much RAM is present?

What devices are available?

Where are they mapped?

Which drivers should bind to them?

The main key component here is that the kernel gets to stay relatively generic, and the board description itself lives outside the kernel. This separation can allow a single Linux kernel image to boot across many boards, only changing the board description itself.

Anatomy of a Device Tree

Here’s a simplified example of what a generic device tree might look like:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

/dts-v1/;

/ {

compatible = "vendor,my-board", "vendor,my-soc";

memory@80000000 {

device_type = "memory";

reg = <0x80000000 0x40000000>; /* 1 GB */

};

cpus {

#address-cells = <1>;

#size-cells = <0>;

cpu@0 {

device_type = "cpu";

compatible = "arm,cortex-a53";

reg = <0>;

};

};

soc {

compatible = "simple-bus";

#address-cells = <1>;

#size-cells = <1>;

ranges;

uart0: serial@9000000 {

compatible = "ns16550a";

reg = <0x09000000 0x1000>;

interrupts = <5>;

clock-frequency = <24000000>;

};

};

};

Let’s take a look at what’s going on, going line by line.

/dts-v1/;

This is just a header that tells the compiler (dtc) what kind of source file this is. It’s the device tree equivalent of a “magic number.”

/ { ... }

Everything lives under the root node. Think of this as “the whole machine.” Inside the root you’ll usually see:

Top-level metadata (compatible, model, etc.)

Memory nodes

CPU nodes

One or more buses (SoC internal bus, external buses, etc.)

compatible = "vendor,my-board", "vendor,my-soc";

This is one of the most important properties in the whole file.

It’s an ordered list of identifiers that tells the kernel what this board is and what it is compatible with. The ordering here actually matters, too, so if you are actively writing one of these, be careful! The kernel and drivers will try to match the most specific string first. A common pattern is:

board-specific: “vendor,board-revA”

family fallback: “vendor,board-family”

SoC fallback: “vendor,socname”

This is similar in spirit to PCI IDs, but instead of the device self-reporting, the platform description reports it.

memory@80000000 { ... }

1

2

3

4

memory@80000000 {

device_type = "memory";

reg = <0x80000000 0x40000000>; /* 1 GB */

};

The node name memory@80000000 is a convention: name@unit-address.

device_type = "memory" is legacy-ish but still a common line item you might find in device trees to describe what type of device we are referring to. In this case, we are referring to memory.

reg describes the address range for RAM. It is a list of address/size pairs. Here it means the base address starts at 0x80000000 and is 0x40000000 long. So the kernel learns: “RAM lives at 0x80000000 and is 1 GiB long.”

cpus { ... } and cpu@0 { ... }

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

cpus {

#address-cells = <1>;

#size-cells = <0>;

cpu@0 {

device_type = "cpu";

compatible = "arm,cortex-a53";

reg = <0>;

};

};

The cpus node is self-describing and is a container for CPU entries.

#address-cells and #size-cells define how child nodes encode their reg. In this example, CPU IDs are one cell wide, and CPUs don’t have “size”.

cpu@0 describes CPU 0 (the first CPU in the list), device_type explains it is a CPU (a bit reduntant in this case, but there are cases where we could be talking about an npu), compatible describes that SoC family it is compatible with, and reg = <0>; is the CPU’s hardware ID/index, usually containing a platform-specific meaning. On real systems, you’ll often see multiple CPU nodes (cpu@0, cpu@1, etc.), plus additional properties like how cache is organized across L1, L2, L3, etc.

soc { ... }

This block is where embedded DTs get interesting because this is where devices within the SoC interact with each other, essentially defining the region where the hardware devices are mapped into memory:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

soc {

compatible = "simple-bus";

#address-cells = <1>;

#size-cells = <1>;

ranges;

...

};

This is telling the kernel that “Children of this node are devices on a memory-mapped bus.”

compatible = "simple-bus" is a generic Linux convention meaning:

“This node is a simple bus; just enumerate its children.”

#address-cells/#size-cells define how address cells are encoded for devices under it, and their sizes.

ranges; (with no value) is a shorthand that means “child addresses map 1:1 to parent addresses, so no extra translation is needed.”

In many SoCs, the soc node is really “the internal peripheral address space.” Remember when I said this defines the region where HW devices are mapped into memory? The uart defined here is a perfect example.

uart0: serial@9000000 { ... }

1

2

3

4

5

6

uart0: serial@9000000 {

compatible = "ns16550a";

reg = <0x09000000 0x1000>;

interrupts = <5>;

clock-frequency = <24000000>;

};

This describes the UART of the system.

uart0: is a label. That label lets other parts of the device tree refer to this node using phandles (like pointers). Even if you’re not using it yet, it’s common practice to label important devices.

serial@9000000 is the node name. Again we see the name@unit-address convention.

compatible = "ns16550a" is the driver binding key. The kernel will match this against drivers that declare: “I support ns16550a compatible devices.”

reg = <0x09000000 0x1000> is the device’s register block is memory-mapped at. So it is located at region 0x09000000 and is 0x1000 in size. This means a driver can ioremap that region and talk to the UART registers.

interrupts = <5> is intentionally simplified in this snippet. In real device trees, interrupts are almost always described relative to an interrupt controller, often looking like:

1

2

interrupt-parent = <&gic>;

interrupts = <0 37 4>; /* type, number, flags */

However, the main thing I want to show is that this is where the DT is declaring which interrupt line this device uses.

clock-frequency = <24000000> Some drivers need to know the input clock to compute baud rates. In newer device trees, you’ll often see this modeled more explicitly using the common clock framework:

1

2

clocks = <&osc24m>;

clock-names = "uart";

But clock-frequency still shows up in simpler examples and older bindings, so I figured our simple example can stick with that.

And there you have it - a basic, albeit generic, device tree for a system. Looking at this example, it’s easy to assume they’re fairly easy to read, and they are for the most part. It’s getting all of the intricacies correct where your device tree tweaking will truly make or break your build.

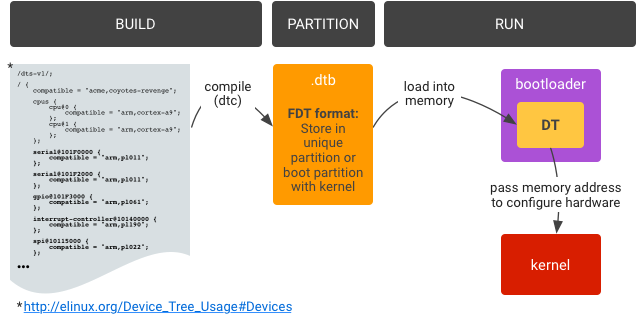

Filetypes and Compilation

When people first encounter device trees, one of the more confusing aspects is the number of file types involved: .dts, .dtsi, .dtb, and sometimes even overlays. Understanding what these are and how they relate goes a long way towards demystifying the whole system.

Figure 4: Device tree overlays

.dts - Device Tree Source

A .dts file is the top-level, human-readable description of a specific board - just like what we got done going through in the previous section. This is the file that usually corresponds to an actual piece of hardware you can buy and hold. It describes things like which SoC is used, which peripherals are enabled, how the board is wired, what external devices are present, and so on.

A .dts almost always pulls in one or more .dtsi files and then adds or overrides details to match the board.

Think of .dts as “this exact board we are building.”

.dtsi - Device Tree Include

A .dtsi file is a reusable include file. It is never meant to stand alone or be compiled directly. Common uses for .dtsi files include SoC-level descriptions (buses, IP blocks, interrupt controllers), shared board-family definitions, and common peripherals used across multiple boards.

For example, a vendor might provide:

socname.dtsi- describing the SoCboard-common.dtsi- shared wiring

Commonizing these interfaces allows for someone to easily extend and override certain aspects of these in the actual .dts. These would then be used to make something like board-revA.dts and board-revB.dts which contain specific, customized variants of those boards.

This actually mirrors how the hardware itself is typically designed, too. Common silicon chips plus board-specific wiring all get rolled into one neat little package.

.dtb - Device Tree Blob

A .dtb is the compiled, binary form of the device tree. It is what the bootloader passes to the kernel. The kernel never sees .dts or .dtsi files. It is architecture-independent binary data that it actually sees. The conversion is done using the Device Tree Compiler by running something like the following command:

1

dtc -I dts -O dtb board.dts -o board.dtb

In most build systems (Yocto, for example), this step happens automatically through a recipe.

.dtbo - Device Tree Overlays

Overlays are compiled device trees meant to be applied on top of a base DTB at boot time. They are commonly used for add-on boards, expansion headers, optional peripherals, and so on.

An overlay is written as a .dts, compiled into a .dtbo, and then merged with the base device tree by the bootloader. While powerful, overlays assume the base device tree is already correct, and as such, are simply a tool for extension and not foundational hardware description.

By the time Linux starts, all .dts and .dtsi files are gone, all includes are resolved, overlays (if any) are applied, and a single flattened .dtb exists in memory

From the kernel’s perspective, there is just one immutable description of the hardware provided at boot.

I find the following mental model to be the easiest for me:

.dtsifiles describe reusable hardware building blocks.dtsfiles describe specific boards.dtbfiles are compiled artifacts.dtboare incremental extensions

Once you view device trees as a build-time hardware description pipeline rather than runtime configuration, the file types stop feeling arbitrary and start making sense, in my opinion.

How do Device Trees get Created?

Bit of a side tangent here, but one common question is asking how one goes about creating a device tree in the first place. In reality,aA device tree isn’t something you can truly auto-generate or come up with on the fly. It’s a description of how the board is physically wired, and that knowledge doesn’t come from knowledge of the Linux kernel. Instead, it comes from hardware design documents created by the hardware manufacturers themselves.

To write a correct device tree from scratch, you need things like:

Clock/reset topology (what feeds what, what needs enabling)

Pin mux configuration (which pins are routed to which peripherals)

Board-level wiring, which devices are actually populated on I2C/SPI, which UART goes to the debug header, which GPIO drives the LED, etc.

Power rails/regulators, PMIC configuration, and “power-good” sequencing

The list goes on and on. That’s why, in the real world, device trees come from the same place BSPs come from: the people who know the intimate details about the hardware.

The typical split of responsibilities is that the SoC vendor provides a .dtsi include file describing the SoC’s built-in IP blocks (addresses, bus layout, interrupt controller, available peripherals).

And then the board vendor/community provides a .dts that essentially “instantiates” the board, creating a .dts that describes which peripherals are used, how pins are muxed, what external chips exist, and how everything is connected.

End users mostly tweak things like enabling a disabled peripheral, adjusting a GPIO, adding a sensor on an I2C header, or applying a device tree overlay for an add-on board. They rarely, if ever, are working on creating the .dtsi or primary .dts that gets used.

If Linux doesn’t already have a working device tree for your board, the missing piece usually isn’t simply writing something like a driver. The reason is much more fundamental. Without it, the kernel has no idea what hardware exists or how it is wired. So for example, without it, the kernel won’t know where devices are mapped, which means drivers won’t probe because compatible nodes aren’t present, clocks and resets would never be enabled, and registers may never even turn on.

It is possible to tweak and extend device trees as an end user, but initial creation is usually a board-vendor/SoC-vendor/community BSP responsibility.

What about Loading?

So we have the fully compiled device tree binary. It perfectly describes our hardware, but what do we do with it from here?

The short answer is that the bootloader is responsible for getting the device tree into memory and handing it to the kernel. How that happens varies by platform, boot flow, and vendor, but the responsibility is always the same.

The Bootloader’s Role

Before the Linux kernel starts executing, several things must already be true:

RAM must be initialized

The kernel image must be loaded into memory

The device tree blob must be available in memory

The kernel must be told where that device tree lives

On most ARM systems, this is handled by a bootloader such as, U-Boot, TF-A + U-Boot, or vendor-specific firmware. The bootloader does not interpret the device tree in any meaningful way. It simply loads the DTB from storage, optionally applies overlays or fixups, and passes a pointer to the kernel at boot.

From the kernel’s perspective, the DTB just “appears” at a known memory address.

Where the device tree lives

Unlike the kernel image, the device tree doesn’t have a single universally mandated storage location. Common approaches include a standalone .dtb file in a boot filesystem (e.g., /boot), a dedicated partition containing one or more DTBs, embedded into a boot image alongside the kernel, selected dynamically based on board ID or revision, and probably more that I have yet to encounter.

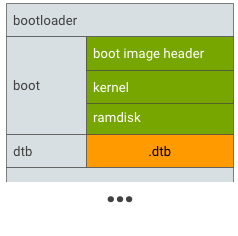

Figure 5: Device tree dedicated partition

Some systems, for example, often use a device tree overlay (DTO) partition, as shown in the figures above. This allows a base device tree to describe the SoC, board or revision-specific overlays to be applied at boot so the same kernel image to support multiple hardware variants.

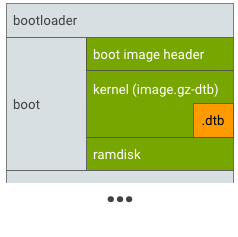

Figure 6: Device tree alongside kernel

Others take a more end-user customizable approach where the generated device tree lives alongside the kernel itself. Most dealing with Xilinx systems or other embedded-oriented boards will typically see it like this.

In many boot flows, the bootloader selects the correct device tree at runtime. Bootloaders may also apply fixups before handing the DTB to the kernel. These fixups allow a mostly static device tree to adapt to minor runtime differences without being regenerated.

Hand-off to the kernel

Once loading and fixups are complete, the bootloader passes control to the kernel along with the kernel command line and the address of the device tree blob.

From that point on, the device tree is read-only as far as Linux is concerned. The kernel parses it during early boot, builds its internal device model, and uses it to bind drivers. After this stage, the device tree is no longer active, as it’s simply the data source that informed kernel initialization.

Once you understand that the device tree is just another boot artifact, kinda like the kernel image itself, then the overall design becomes much easier to reason about.

What Can I do as an End User with Yocto?

If you’re using Yocto, you’re not usually the person making a device tree. Yocto sits at an interesting boundary; it’s not firmware development, but it’s also far closer to the hardware than most Linux users ever get. As an end user (or integrator) working with Yocto, your role is typically to select, extend, and validate device trees, not to design them from scratch.

Select the correct device tree for your board

Most BSP layers provide multiple DTBs for a single SoC family. For example, there may be different board revisions, different SKUs, evaluation boards, production boards, etc.

In Yocto, this is usually handled via MACHINE and KERNEL_DEVICETREE. Your first and most important task is simply making sure the kernel is booting with the correct DTB for the hardware in front of you. Many “Linux doesn’t work” issues are actually “wrong device tree selected” issues.

Patch or extend an existing device tree

A very common Yocto workflow is to append to an existing device tree rather than replacing it outright. Typical examples include enabling a disabled peripheral, adjusting pin muxing for a custom carrier board that nearly matches the one you’re working on, adding an I2C or SPI device that exists on your design but not the reference board, correcting GPIO polarity or interrupt flags, and so on.

In Yocto specifically, this is usually done by adding a .bbappend to the kernel recipe, including patched .dts or .dtsi files in your BSP layer, rebuilding the DTB as part of the custom kernel build, etc.

At this level, you’re still relying on vendor-provided hardware descriptions. The main thing is you’re just tailoring them to your board.

Manage device trees as BSP artifacts

In a Yocto project, device trees should be treated as board support data, not application configuration. That means they live in BSP layers, they’re version-controlled alongside kernel config, and changes are reviewed like any other hardware-related modification.

This also makes it easier to support multiple boards with the same distro: one kernel, multiple DTBs.

Use overlays carefully (when appropriate)

Yocto can support device tree overlays, but they should be used with restraint. Overlays are well-suited for optional hardware modules, expansion boards, and small, well-contained changes.

They are not a substitute for a correct base device tree. If you find yourself stacking overlays to fix core platform behavior, that’s usually a sign that the base DT needs to be corrected instead.

Debug device tree issues effectively

As a Yocto user, you don’t need to guess whether a device tree change worked. Linux is filled with useful tools to assist you in debugging, such as:

/proc/device-tree/to inspect what the kernel actually seesdtc -I fsto dump the live device treedmesgto verify driver probe and resource assignmentKernel warnings about missing clocks, resets, or interrupts

Being able to read a DTS and correlate it with kernel logs is one of the most valuable embedded Linux skills you can develop because it will help you be able to better narrow down where issues might be occurring.

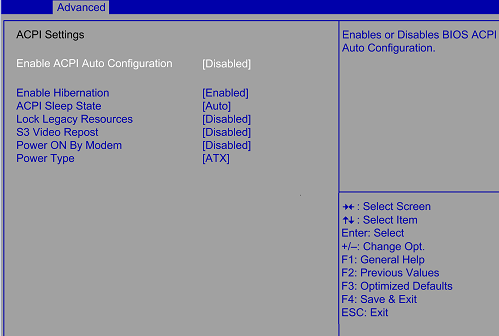

Why no ACPI for ARM?

Figure 7: What is ACPI?

So now we get to the big elephant in the room. Why do we have to go through all of this manual nonsense when things “just work” on x86? Well, strictly speaking, this question is slightly misleading: ACPI does exist on ARM. Modern ARM systems can and do boot using UEFI and ACPI. Windows on ARM is the most visible example, and some ARM servers also rely on ACPI rather than device trees. It’s even in the Linux kernel docs.

So the real question isn’t, “Why doesn’t ARM support ACPI,” but rather, “Why hasn’t ACPI become the dominant solution for ARM Linux systems?”

The core issue is not technical feasibility, but rather an ecosystem reality. ACPI assumes a very specific model:

A fairly complex firmware layer

Vendors that implement the specification correctly and consistently

AML bytecode that the OS must interpret at runtime

A strong, enforced contract between firmware and OS

In the x86 world, this works because vendors are heavily incentivized to follow the rules. If ACPI is broken, Windows doesn’t boot, and that’s a total non-starter. You can bet your bottom dollar that both Microsoft and Intel will be on you to fix it, and fast.

In the ARM world, especially the truly embedded one, those incentives historically haven’t existed. Many ARM platforms ship minimal firmware, lack the engineering resources to maintain complex ACPI tables, and treat firmware as a “good enough to boot” interface.

As a result, ACPI tables provided by ARM vendors are often incomplete, inconsistent across revisions, and tightly coupled to a specific OS version. Linux can consume ACPI on ARM, but only if the firmware is trustworthy. In many embedded systems, it simply isn’t.

Device trees avoid this entire class of problems by being static, declarative, human-readable, and version-controlled alongside the kernel or BSP. Instead of executing firmware-provided bytecode at runtime, Linux is handed a data structure that describes the hardware as-is. That tradeoff has proven far more robust in the embedded ecosystem.

The Future of ARM

Figure 8: Generic Operating System Interoperability

ARM is well-aware of these fragmentation issues which is why initiatives like ARM SystemReady exist. SystemReady aims to do for ARM what decades of pressure did for x86:

Define minimum firmware requirements

Mandate UEFI and ACPI compliance

Ensure a generic OS image can boot across vendors

Reduce board-specific glue code

For ARM servers and higher-end platforms, this direction makes a lot of sense. It enables distro-style Linux installs, standardized boot flows, and overall less vendor-specific BSP work.

However, the debate between ACPI vs device trees doesn’t disappear; it just shifts the responsibility. Many embedded developers still ask questions like, “Do we really want to replace a simple, declarative hardware description with a complex firmware interface that vendors may only partially implement?”

Device trees are not elegant, but they are explicit. They make wiring mistakes visible, debuggable, and reviewable. ACPI, by contrast, hides behavior inside firmware logic that is often opaque and difficult to inspect.

The world we currently live in is a bit of a split. Servers and high-end ARM platforms gravitate toward UEFI + ACPI, while embedded and custom hardware continue to rely on device trees.

Linux supports both because it has to. Rather than one replacing the other, ACPI and device trees reflect two different philosophies of platform design. ARM didn’t fail to adopt ACPI; it simply grew in an environment where the assumptions ACPI depends on were never guaranteed, so it had to walk its own path as it matured.

Wrapping Up

Hopefully this post helped answer some common questions and provided a clearer view into both the history and motivation behind device trees, as well as where the ecosystem appears to be heading.

In my opinion, it’s unlikely that ARM, RISC-V, or other architectures primarily targeting embedded developers will converge on a single ACPI-esque solution that fully replaces device trees. Embedded hardware is simply too customizable and too diverse compared to the relatively standardized x86 platform.

For those of us working closer to the hardware, this means understanding both worlds. Initiatives like ARM SystemReady will continue to push standardization on the server and higher-end platforms, enabling more generic operating system support. At the same time, the embedded space will continue to rely on explicit, declarative hardware descriptions to handle the wide range of designs and use cases that exist today. In either case, Linux is guaranteed to support both models, so kernel devs can always be ready no matter which method is chosen.

Further Reading

Some useful links on device trees:

Happy firmware hacking!