Looking Around Logs

Revisiting classic expressive programming languages for scripting

Imagine a scenario where you’re parsing a log, and you need to extract certain portions of data out of it. What tool do you reach for these days? Despite concerns about readability, most of us reach for regular expressions when faced with text parsing. Regular expressions have been a powerful tool in developers’ toolboxes ever since they appeared in Ken Thompson’s rewritten version of QED.

Most people today, including myself, probably reach for their favorite robust scripting language and have at it. Today’s languages of choice tend to be things such as Python, Rust, Go, and whatever JavaScript library happens to be the flavor of the week. 😊

The thing is, Perl has long been regarded as a language that takes regular expressions to the next level. Dubbed a Swiss-Army Chainsaw and the “duct tape” of the Internet, Perl’s capabilities around regular expressions still have few rivals in 2024.

One of Perl’s secret weapons that many modern day languages like to take inspiration from is its support for zero-length assertions such as lookaheads and lookbehinds, collectively known as lookarounds. These assertions allow you to match patterns based on context without actually consuming characters, making your regular expressions more precise and expressive.

In this post, we will dive into Perl’s implementation of lookaround assertions. We’ll explore what they are, when to use them, and why Perl remains one of the most copied tools for these advanced regex patterns. We’ll also compare these to more straightforward approaches in scripting such as trying to reach for sed or awk, the benefits of lookarounds, potential pitfalls, and more. Note that this post assumes the reader already has a general understanding of regular expressions, but I’ll try to touch on some general basics just in case.

What is Perl?

Perl is a high-level, general-purpose programming language known for its text-processing capabilities. Created by Larry Wall, Perl quickly gained popularity because of its flexibility with regular expressions, making it a go-to language for parsing and manipulating text data. When CGI scripting became popular, giving developers the ability to generate dynamic web content, it established itself as the de facto scripting language of the Internet. Even though newer languages like Python, JavaScript, and Go have diminished Perl’s dominance as the primary scripting language for the Internet, Perl’s regex engine remains one of the most powerful out there even in 2024.

Understanding Lookahead and Lookbehind Assertions

Lookahead Assertions

First, let’s take a look at lookaheads. Lookahead assertions allow you to match a string only if it is followed by a certain pattern. Lookahead is non-consuming, meaning it checks for a condition without including that condition in the match.

Syntax

In Perl, lookahead is denoted with (?= ...) for positive lookahead and (?! ...) for negative lookahead. A positive lookahead checks if a certain pattern can be matched ahead in the string without actually including it in the match, while a negative lookahead checks that a certain position does not follow the current position in the string.

Lookahead Basic Example

Suppose you want to match a word only if it is followed by a number. Here’s our string we’ll use as an example: apple123 banana grape456

In this example, we want to grab the words apple and grape. Let’s first start with what most programmers would reach for. We can do this with grep and sed with a bit of regex-fu:

1

2

text="apple123 banana grape456"

echo "$text" | grep -o '[a-zA-Z]\+[0-9]\+' | sed 's/[0-9]\+//g'

But because Perl has capabilities that mimic sed and grep, we can do this same operation with a single command:

1

2

3

4

my $text = "apple123 banana grape456";

while ($text =~ /([a-zA-Z]+)(?=\d)/g) {

print "$1\n"; # Outputs "apple" and "grape"

}

In this example, the words apple and grape are matched because they are followed by a number. Notice that the number itself is not captured as part of the match. That’s part of the beauty of lookarounds. We are able to match a pattern and grab only the portion we need with little overhead.

While some of this will probably be review for those familiar with regular expressions, we’ll go through it in detail just in case. This explanation will also help if you were confused during the grep and sed example above. The breakdown of the regex is as follows:

([a-zA-Z]+):[a-zA-Z]is a character class that matches any uppercase or lowercase English letter.- The

+quantifier means “one or more occurrences” of the preceding character class. So,[a-zA-Z]+matches one or more letters. - The parentheses

()around[a-zA-Z]+create a capture group. This means that whatever matches this pattern is captured for later use.

(?=\d):- This is a lookahead assertion. It checks if what follows the current position in the string is a digit (

\d). - The lookahead does not consume any characters, meaning it only verifies the presence of a digit without including it in the match.

- In the previous

grepandsedexample, we had to use a character class that only grabbed the digits 0 through 9 and had to apply it multiple times. With Perl, this single lookahead handles both instances efficiently.

- This is a lookahead assertion. It checks if what follows the current position in the string is a digit (

/gmodifier:- The

gmodifier stands for “global,” which allows the regex to find all occurrences in the string, not just the first one.

- The

Lookahead Further Example

Consider a scenario where you want to match and extract all words that are followed by a four digit sequence:

1

2

3

4

my $text = "apple1234 banana grape456 orange7890 pear2468";

while ($text =~ /(\w+)(?=\d{4})/g) {

print "$1\n"; # Matches apple, orange, and pear

}

In this example, it will output apple, orange, and pear. Let’s break down the regex:

(\w+):- The

\wcharacter class matches any “word” character, which includes letters (both uppercase and lowercase), digits, and underscores. - The

+quantifier means “one or more occurrences” of the preceding character class. So,\w+matches one or more word characters.

- The

(?=\d{4}):- This is a lookahead assertion that checks if what follows the current position in the string is exactly four digits.

- The

{4}is the quantifier that explicitly specifies that there must be exactly four digits(\d)following the matched word. Without this, it can match any possible digit.

The while loop iterates through the string, capturing words that are immediately followed by a four-digit sequence, and successfully grabs. apple, orange, and pear because these words are followed by 1234, 7890, and 2468, respectively.

However, there are some slight drawbacks, as this isn’t quite as intuitive as it might seem. For example, let’s say we wanted to match any word that contained any number of digits after it. You might think that we would need to simply remove the {4} and keep everything else. After all, \d matches all digits, and the + quantifier will extend it to be one or more digits. Let’s try that:

1

2

3

4

my $text = "apple1234 banana grape456 orange7890 pear2468";

while ($text =~ /(\w+)(?=\d+)/g) {

print "$1\n"; # What will we match here?

}

In this case, you might expect to get words like apple, grape, orange, and pear. However, we would actually get apple123, grape45, orange789, and pear246. Not only do we get the word with digits, but every matching word grabbed contains a missing digit. Let’s break down why:

- Initial Match Attempt:

- The regex engine starts at the beginning of the string and matches

\w+as much as possible. Forapple1234,\w+matchesapple1234.

- The regex engine starts at the beginning of the string and matches

- Lookahead Check:

- The lookahead

(?=\d+)checks if there are digits following the current match. Since\w+consumed all characters including the digits, the lookahead fails because there are no digits left to match.

- The lookahead

- Backtracking:

- The regex engine backtracks one character at a time from the end of the current match. It reduces the match to

apple123and checks the lookahead again. This continues until the lookahead finds a digit to match.

- The regex engine backtracks one character at a time from the end of the current match. It reduces the match to

The resulting matches end up being apple123, grape45, orange789, and pear246. Each match is missing a digit because the last digit is what allows the lookahead to succeed.

To correct this, we need to use a less greedy character class. Using the initial example’s ([a-zA-Z]+) will allow this to successfully match apple, grape, orange, and pear.

The point here is that you need to be careful when combining certain character classes together, as the results might not be exactly what you would expect if you didn’t pay close attention to the documentation.

Lookbehind Assertions

Lookbehind assertions allow you to match a string only if it is preceded by a certain pattern. Like lookahead, it is non-consuming, meaning it checks for the presence of a condition without including it in the final match.

Syntax

In Perl, lookbehind is denoted with (?<= ...) for positive lookbehind and (?<! ...) for negative lookbehind. Like with lookaheads, lookbehinds follow a similar operation. A positive lookbehind checks if a certain pattern can be matched behind in the string without actually including it in the match, while a negative lookbehind checks that a certain position does not precede the current position in the string.

Lookbehind Basic Example

Let’s go back to our first example. Suppose you want to match a number that is preceded by the word “grape”:

1

2

3

4

my $text = "apple123 banana grape456";

if ($text =~ /(?<=grape)(\d+)/) {

print "$1\n"; # Outputs "456"

}

Here, 456 is matched because it is preceded by grape. The word grape itself is not captured, and we only get the digits.

Lookbehind Further Example

Consider a scenario where you need to find an email for business-related inquiries, but it’s buried in a text doc that you can’t easily parse because it was scraped by a web crawler without your input. The only situation you might know is that you’re looking for a potential business inquiries email, and they normally have the email after a colon. You could do something like the following here:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

my $text = 'Reach out to us with one of our many emails. ' .

# Imagine many different types of emails

'customer service: cs@company.com. ' .

# Imagine many lines of text before here

'business inquiries: business@company.com. ' .

# Imagine many lines of text after here

'established business customers: insider@company.com ' .

'general questions: ask@company.com ' .

# They even throw in certain notes about business inquiries that

# makes it a bit more difficult to just grep for business inquiries

'Note business inquiries and established business is separate. ' .

'Do not email insider@company.com for business inquiries.';

while ($text =~ /(?<=business inquiries:[ ]{1,10})\S+@\S+\.\S+\b/gi) {

print "Matched business inquiries email: $&\n"; # Outputs "Matched business inquiries email: business@company.com"

}

Let’s run through the regex:

(?<=business inquiries:[ ]{1,10}): Lookbehind assertion ensuring the match is preceded by “business inquiries:” and 1-10 spaces\S+: Matches one or more non-whitespace characters (the prefix of the email)@: Matches the “@” character in email addresses\S+: Matches one or more non-whitespace characters (the domain of the email)\.: Matches a literal dot, separating the domain from the top-level domain\S+: Matches one or more non-whitespace characters (the top-level domain)\b: Ensures that the email address is complete and followed by a non-word character

Caveats

There are some drawbacks to lookbehinds, however. The biggest is that not all versions of Perl have them fully implemented to be able to use with variable-length lookbehinds. Some allow for experimental support (v5.30+), some limit pattern matching up to 255 characters, and some don’t offer it at all. You’ll want to exercise some caution when using variable-length lookbehinds, especially if there might be a legacy version on your system. You might want to consider using \K instead.

Here’s an alternative variant using \K to get around this issue with the above example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

my $text = 'Reach out to us with one of our many emails. ' .

'customer service: cs@company.com. ' .

'business inquiries: business@company.com. ' .

'established business customers: insider@company.com ' .

'general questions: ask@company.com ' .

'Note business inquiries and established business is separate. ' .

'Do not email insider@company.com for business inquiries.';

while ($text =~ /business inquiries:\s*\K\S+@\S+\.\S+\b/gi) {

print "Matched business inquiries email: $&\n";

}

For more in-depth info on this specific topic, Brian Foy has a great write up on it here.

Realistic Scenario: Parsing Logs with Lookarounds

Consider a scenario where you have a web server log file, such as an Apache log, and you want to extract specific information from it. Let’s say the log file has hundreds of thousands of entries like this:

1

2

3

127.0.0.1 - john_doe [10/Oct/2024:12:45:33 +0000] "GET /admin/resource_1234 HTTP/1.1" 404 512 "-" "Mozilla/5.0"

192.168.1.1 - jane_smith [10/Oct/2024:12:50:00 +0000] "GET /user/resource_5678 HTTP/1.1" 200 1024 "-" "Mozilla/5.0"

127.0.0.1 - alice [10/Oct/2024:12:55:45 +0000] "GET /admin/resource_9999 HTTP/1.1" 404 256 "-" "Mozilla/5.0"

Your goal is to extract the usernames from entries that contain the path /admin/ and return a 404 status code. In this case, it would be john_doe and alice. Let’s try this with a few popular methods. We won’t be going into detail on all of these like before, but I have provided some links at the end that might help for further reading.

Using Sed

Using sed for this task can work decently well if you’re familiar with regex. However, it can also be a bit cumbersome because sed is line-oriented and lacks the ability to perform lookbehind operations directly.

You would need to chain multiple commands to approximate the behavior:

1

sed -n '/\/admin\// s/.*- \([^ ]*\) \[.*\] ".*" 404 .*/\1/p' logfile.txt

While this command works, it might not be very readable to some, and it requires some careful crafting of the pattern. It also cannot easily handle variable-length lookbehind, limiting future flexibility.

Using Awk

awk provides more flexibility compared to sed, but it still struggles with complex lookahead and lookbehind scenarios:

1

awk '/\/admin\// && / 404 / { match($0, /- ([^ ]*) \[/, arr); if (arr[1] != "") print arr[1]; }' logfile.txt

This awk command attempts to match the conditions, but the complexity increases as we add more context-based requirements. It isn’t terrible, but one could argue the readability and maintainability of the command suffer as the conditions get more complex.

Using Perl

Using Perl with lookahead and lookbehind makes this task significantly easier and more readable:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

my $logfile = "logfile.txt";

open my $fh, '<', $logfile or die "Could not open file: $!";

while (my $line = <$fh>) {

if ($line =~ /(?<=- )([^ ]+)(?= \[.*\] "GET \/admin\/.*" 404 )/) {

print "$1\n";

}

}

close $fh;

This regex uses both positive lookbehind and positive lookahead together.

- Positive Lookbehind

(?<=- ):- This asserts that what precedes the current position in the string is

-. This part does not consume characters; it only checks that the string before the current match contains-.

- This asserts that what precedes the current position in the string is

- Capture Group

([^ ]+):- This captures one or more characters that are not a space (

[^ ]means “any character except a space”). This part effectively captures the text that follows the-until the next space.

- This captures one or more characters that are not a space (

- Positive Lookahead

(?= \[.*\] "GET \/admin\/.*" 404 ):- This asserts that what follows the captured group is a space, followed by square brackets containing any characters

(\[.*\]), followed by a space, the string"GET /admin/.*"(matching any request to/admin/), and then a space, and404.

- This asserts that what follows the captured group is a space, followed by square brackets containing any characters

The regex is semi-readable, and for those who have learned about lookarounds, the lookahead/lookbehind mechanism makes it clear what context we are looking for without consuming unnecessary portions of the line. I say semi-readable as someone who hasn’t studied regular expressions may struggle with this at first glance, but the power comes from its ability to expand on this in a safer manner than the sed or awk versions.

Using Python

Python also has a capable regex engine, though it has some limitations compared to Perl, particularly with variable-length lookbehinds. However, this task can still be handled effectively in Python using the re module fairly easily:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

import re

with open('logfile.txt', 'r') as logfile:

for line in logfile:

match = re.search(r'(?<=- )([^ ]+)(?= \[.*\] \"GET \/admin\/.*\" 404 )', line)

if match:

print(match.group(1))

In this Python example, we use the re module with lookaround assertions to extract the desired usernames. Python’s regex syntax is similar to Perl’s because it took direct inspiration from Perl. In fact, the docs say so at the very top. But as I was reading the documentation, I started noticing the Python devs would deviate from Perl for one reason or another which is what started this entire spiral down the rabbit hole of learning Perl’s regex syntax and how it works compared to the Python variants.

It turns out that, even in 2024, there are still certain regular expressions that Perl does which other languages either cannot or choose not to.

Dangers and Drawbacks of Lookarounds

Lookarounds are powerful, but like any regular expression, they should be used cautiously for a few reasons:

- Performance Impact: The non-consuming nature of lookarounds can make regex evaluation slower, especially when used in complex patterns or on large text bodies.

- Readability Concerns: While they can make the intent of a match clearer, they can also lead to confusing regex patterns that are hard to maintain if overused.

- Limited Support: Not all regex engines support advanced lookahead and lookbehind. Even different versions of Perl, for instance, lack support for variable-length lookbehinds, which can make porting regex patterns across different versions of Perl a possible surprise for the one executing the scripts.

Is Perl Still Viable Today

Many modern languages, like Python, JavaScript, Go, and so on have incorporated many of Perl’s rich regular expression support, such as lookarounds. However, they may also come with various restrictions compared to the Perl version.

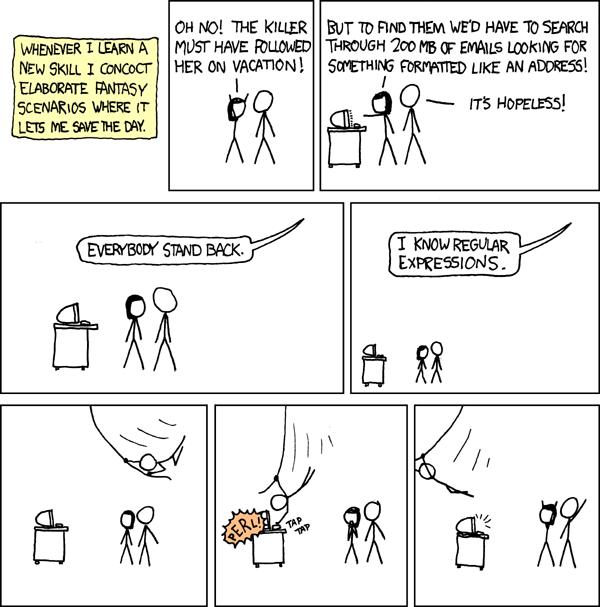

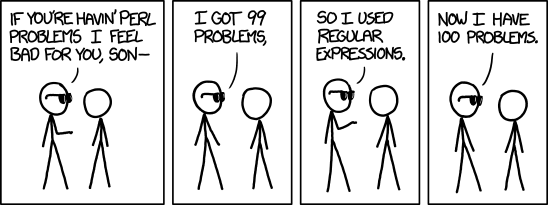

Does this mean people should look to using Perl for rich text parsing? To be honest, that is up to the individual programmer or team. Perl certainly has its drawbacks, quirkiness, and it’s easy to get lost in a clever regex that solves an immediate problem, yet is unreadable for future devs simply due to lack of exposure. Perl’s expressive matching capabilities and robust text processing offers many advantages, but there’s a reason why the memes like this exist:

And this:

Whatever you decide to choose, as always, make sure you do your proper research into it, understand your business case, and try to make the best decision for your project.

Further Reading

Some useful links that helped me:

- Perl Regex Documentation

- Python Regex Documentation

- Regular Expressions Tutorial - Lookahead and Lookbehind Assertions

- GNU sed Manual

- GNU awk Manual

Happy scripting!